ABSTRACT In the context of the never-ending story cycle of the 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act this post considers the perennial question of why the poor have so often throughout history been considered resistant to policy reforms that were designed in their own interests. As an alternative to the deficit model of human reasoning which imagines people discarding old habits in response to the provision of new, better or more digestible information I suggest that new schemes and policies struggle to recruit when they are poorly adapted to the way people in targeted groups live. When Charles Masterman, one of the architects of the 1911 National Insurance Act, the most decisive step toward the establishment of the British welfare state, remarked on the ‘silence’ of the poor he signalled a tendency for policymakers to be detached from the lives they were trying to improve. This is persistently true of financial services targeted at those on low incomes. Industrial life assurance is a case in point, a gigantic industry that flourished despite persistent efforts to curb its excesses. Understanding why and how people consume products that are considered bad, dangerous or toxic is crucial to improving personal and public welfare.

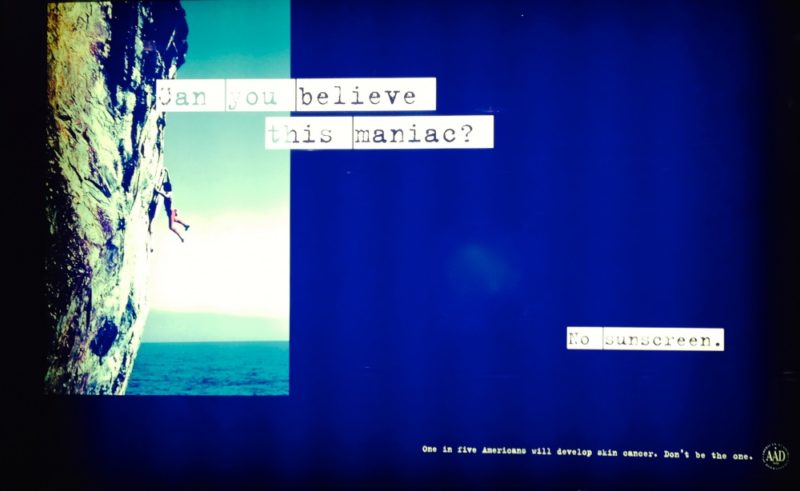

The United States has an almost unhealthy obsession with selling health. Television news programming is interrupted every few minutes by messages promising solutions to COPD, arthritis, Crohn’s disease, erectile dysfunction and in almost the same breath warning of possibly catastrophic side effects, advertisers describe ‘health by numbers’ innovation in health care plans, laser corrective spinal surgery, vitamins to help aging men face the waves and minimally invasive ‘lifestyle lifts’ to keep women’s chronological ages secret. At the same time news media, through the never-ending story cycle of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), have helped maintain health care’s place as a national proxy for debates about the role of government. This flood of mainly political information seems not to have moved many. As Drew Altman, President of the Kaiser Family Foundation notes, almost half of Americans say they still haven’t got an answer to the question that matters most to them: What does the law mean for me and my family?

That lack of answers hasn’t stopped people taking positions on the ACA. Everyone has a view and some are just this side of unregenerate. While the Health Reform Monitoring Survey report released in Spring 2014 was clear that rich, white, healthy people were the group most likely to view the Act unfavourably, uninsured adults who have most potential to benefit, especially those from white and middle income groups, were several shades off enthusiastic. As the report concluded, public outreach efforts do not appear to be reaching the key target populations. In these groups, people’s hearts and minds are not being easily moved. This raises an old and interesting problem. Why are the poor resistant to policy reforms designed in their own interests? Why are target groups slow to discard old habits or adopt new ones that are better adapted to the intertwined private and public goods of better health and greater economic security?

With contradictory surveys, reports and analyses reflecting on the early implementation of the ACA appearing every week it is too soon to say whether strategies to recruit sufficient numbers of the uninsured, especially the healthy 18-35 year old ‘young invincibles’ will ultimately be successful. What is already clear though is that the job has been harder than it should have been. In this, the ACA may be following the path of a series of British policy reforms that were stubbornly resisted by the very people whose lots they were meant to improve. There are many reasons for this (McFall, 2014). One is the persistence of a ‘deficit model’ of human reasoning that imagines people adopting new habits and discarding old ones in response to the provision of new information, education and skills training. [In a Whitehouse accustomed to the gentle nudging of behavioural economic models this seems unlikely to be the ACA’s main barrier.] Another more obdurate one relates to what Charles Masterman, one of the primary architects of the 1911 National Insurance Act (NIA), perhaps the most decisive policy step in the direction of Britain’s post-war welfare reforms, was getting at when he wrote of the poor; And we are very silent, so very silent that no one to this hour knows what we think on any subject or why we think it.

Masterman, like many of his generation of reformers, had spent time in the slums but even he could not speak for the poor. Just how much the NIA was detested by those it was meant to help, bears witness to this. Another indication of the distance between Masterman’s generation and the targets of their reforms was their bewilderment at the continued growth of the commercial industrial life assurance industry. Industrial life assurance (ILA) was first established in Victorian Britain and was based on the door-to-door sale and premium collection of small life insurances. Beginning in the 1840s, the industry was soon trading on a colossal scale with an estimated 42 million policies in force in 1910 and more than 100 million by the 1940s. This was double the British population at the time and possible only because multiple policies were taken out on the same lives. The scale of the industry meant it was the closest thing to a universal system of financial provision and as a direct consequence it was seldom far from the scrutiny of policymakers.

ILA, despite its confusing name, was nothing to do with industrial accidents. It flourished as a means to certain forms of consumption even among the poorest. Little has been written about the consumption habits of the poor but they did, of course, consume. They spent larger proportions of their income on things poverty researchers like Charles Booth and Seebohm Rowntree defined as ‘necessaries’; the rent, food, clothing, fuel and so on; but money was also found for other things, like alcohol, tobacco and gambling. By being consumed even when there were insufficient funds for the necessaries, these other things troubled poverty researchers leaving them often to conclude that there was a wilful element to deprivation among a large section of ‘undeserving’ poor. Townsend’s retort that poverty investigators took little account of working class customs, or that the poor would need to live like ‘skilled dieticians with marked tendencies towards puritanism’ (1954: 134) to reach the nutritional standards that researchers deemed achievable, is an example of how little lived experience has figured in policy intervention. This oversight was especially pronounced in the case of ILA, one of the largest and most reviled forms of ‘non-necessary’ expenditure for almost a century until its most controversial forms began gradually to be legislated away in the late 1940s.

Insurance doesn’t sound like an indulgence, but for many, the percentage of income spent on it, even in the poorest households, was an outrage. It is almost implausible that the hard scrimp necessary to reserve an average of between 5-10% of weekly income was done to meet life insurance premiums. That this was done for a product that struggled for over 150 years to build a market amongst the upper and middle classes; that was complex, possibly unsafe and based on future need when present necessities might have been thought more pressing, is perplexing. At least it is perplexing if the focus is on the product, rather than what it was used for.

ILA grew out of the demand for funeral cover. Its policies did not initially cover lives; they covered deaths, paying out only enough to meet funeral expenses. Funerals mattered differently then, and to the poor they mattered more than any other ritual event and more was spent on them. ILA provided the means for this by offering a product that enabled the poor to access the sums involved. But it wasn’t just the percentage of income spent, or its motivation, that provoked outrage: it was the structure of the whole system. Weekly collection was eye-wateringly expensive to deliver, and for the first few decades an average of around 50% of premium receipts went on administrative expenses. This stoked an argument that the poor were paying far too much for a product that they didn’t need which did little to promote the qualities of thrift, responsibility and independence that they did.

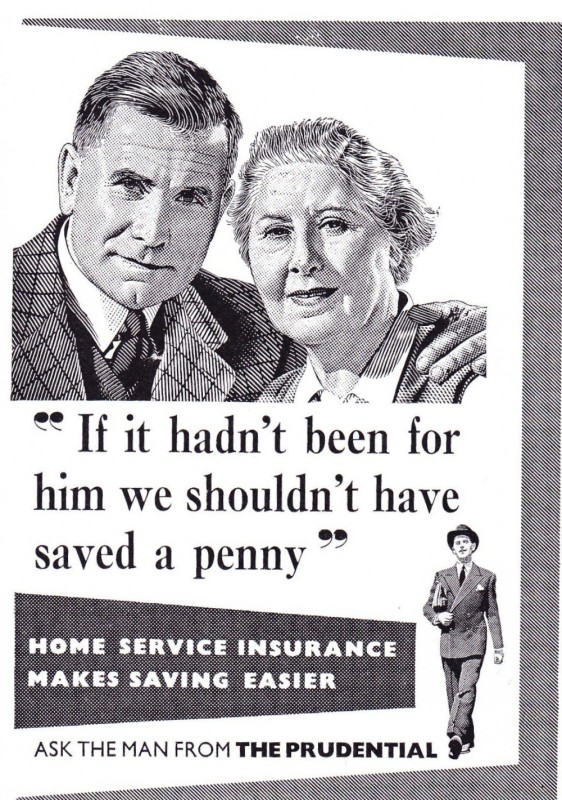

In addition to providing means, ILA is a brilliant example of how a mechanism for mass consumption was devised. With a problem on this scale, in a population that has left scant records behind, an accommodating approach to analysis has its attractions. Many things of many kinds shape consumption. Among these, substantial allowance ought to be made for the planned, technical activities of companies. Thinking of these activities and the equipment to carry them out, opens up the relationship between markets and their devices. In ILA, one single characteristic ‘device’ stands out: doorstep agents.

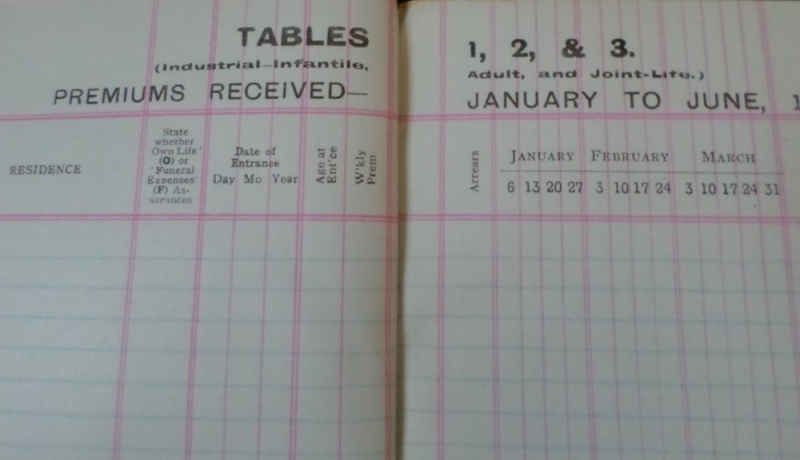

Agents were unquestionably involved in ‘devising’ – they did not just to take a product to market, they built their markets, coaxing and disciplining customers, even becoming themselves part of what was sold. Crucially, they acted as a two-way channel. They collected and sold but they also listened and gathered information and adjusted their performance and the products they offered accordingly. There was more than a hint of carnival in this. In Thomas Cranmer’s Anglican prayer of confession ‘we have followed too much the devices and desires of our own hearts’, devices are part contrivance, motive forces of which even the penitent is not fully aware. Those devising sales too, perform something of a sleight of hand, not necessarily an out and out deception, but a selective, calculated presentation. This presentation takes into account what has already been learnt in previous customer exchanges and interactions, many, but not all, of which were stored in the foremost piece of equipment, the agent’s book.

Agents’ books recorded transactions: payments received and missed, policy types, names, addresses and ages. They did not record a whole host of other relevant things that agents were also trained to watch out for. Signs of opportunity or risk might be almost anything; greetings cards on the mantelpiece, the condition of the house, a worry expressed. Any of this could be added to the store of information that helped connect what agents could offer, to what customers wanted and what they could afford. Agents provided a means of combining the most impressionistic insights with regular transactional data; they brought customer experience into contact with payment histories. This combined record of private details and minute transactions was fed into the bureaucratic machinery of the companies, where it was stored, analysed and used to modify and market further products. The process, at its decades’ long peak, had a vast, mechanical inevitability about it. Customers in their masses were swept into the path taken by all those who had gone before them, to purchase a product that seemed already to contain what they knew: their wishes, their fears, their understanding of the limits of financial possibility.

Whether what customers knew was correct or rational in the financial literacy sense hardly matters. These were products that took account of lived experience; they could be made to fit into lives where extreme financial precariousness was common. Weekly payments were small, taken quickly and could be missed without penalty. These features made saving possible and thereby presented reasonable means to ends that were desired in ways that were fathomable to agents, if not to policymakers. It was the affordances of this machinery that eventually drew Masterman and his colleagues to admit and then rely on ILA companies to administer the NIA. This was a volte-face that hardly anyone – excepting the companies – was comfortable with. It was a step outside of a series of regulative attempts All through its history governments tinkered with the legislative framework surrounding ILA, deciding at times to clean it up and at other times, most famously in the Beveridge report, to get rid of it entirely. None of these efforts changed things in quite the way or to the extent they set out to and none succeeded in terminating the industry.

Whether what customers knew was correct or rational in the financial literacy sense hardly matters. These were products that took account of lived experience; they could be made to fit into lives where extreme financial precariousness was common. Weekly payments were small, taken quickly and could be missed without penalty. These features made saving possible and thereby presented reasonable means to ends that were desired in ways that were fathomable to agents, if not to policymakers. It was the affordances of this machinery that eventually drew Masterman and his colleagues to admit and then rely on ILA companies to administer the NIA. This was a volte-face that hardly anyone – excepting the companies – was comfortable with. It was a step outside of a series of regulative attempts All through its history governments tinkered with the legislative framework surrounding ILA, deciding at times to clean it up and at other times, most famously in the Beveridge report, to get rid of it entirely. None of these efforts changed things in quite the way or to the extent they set out to and none succeeded in terminating the industry.

The primary sticking point was always collection. Collection was what made ILA so expensive and dispensing with it naturally commended itself as the solution to providing affordable protection. The conclusion that the poor should not be paying into such an expensive system, that it was not rational for them to do so, was irresistible. Unfortunately, the question of whether or not the poor should be paying for collection was probably the wrong one when they already were, had been for a long time since, and in such numbers. A better, seldom asked question was why. Collection took account of lived circumstances, it connected offices to policyholders and afforded a easy means of entry, information, feedback, influence and so on – all facilities that government alternatives lacked. Through it, companies maintained a channel that gave them insight into customer experience, to the ways they practiced rationalities and economies adapted to their knowledge of their own situations.

Fundamentally, collection was how companies devised consumption. Collecting exposed agents to the combination of belief, experience and knowledge William James (2000: 40) called the ‘very dirt of private fact’. This conferred a stunning advantage on commercial schemes. If in reason there is always a bit of sentiment, and in sentiment a bit of reason, then the disciplinary vanities that sustain instrumental rationality or deficit modeling as the best explanations of human behaviour are just not that useful. To the extent that market providers devise techniques of sweeping up ‘private fact’ then incorporating it into products and marketing platforms that seem already to know all about us, they have the edge over government schemes designed only to appeal to reason. This is not an anachronistic problem. The health insurance exchanges devised to deliver the ACA that are still striving to recruit enough of the young invincibles to create a sustainable pool of risk know precisely how much appeal matters.

ILA is now a dead sector in the rich democracies where it began (though not everywhere else). Its once omnipresent agents, practices and artefacts are being rapidly forgotten and much of its remaining assets are just waiting in zombie life funds for the final claims to be paid out sometime in the 2040s. The traces of an industry founded on the despairs and hopes of the poor are however knitted everywhere into the built landscape, into the infrastructures of global finance and the histories of health and welfare regulation.

References:

James, W. (2000/1907) What Pragmatism Means, in Gunn, G. [ed.] Pragmatism and other writings, Penguin Classics

McFall, L. (2014) Devising Consumption: cultural economies of insurance, credit and spending. Routledge

Townsend, P. (1954). Measuring Poverty. The British Journal of Sociology, 5, 2: 130-137

A version of this article first appeared in the European Financial Review on August 20 2014