Many Eyes Wordle Many Eyes Wordle http://www-958.ibm.com/software/data/cognos/manyeyes/visualizations/cgap-technology-blog-2010

Many Eyes Wordle http://www-958.ibm.com/software/data/cognos/manyeyes/visualizations/cgap-technology-blog-2006

These wordles from Many Eyes are a visualization of the word frequencies of all the terms in the Consultative Group to Assist the Poor (CGAP) Technology blog, in 2006 and 2010. CGAP is a consortium of government and philanthropic aid organizations, long interested in microfinance opportunities and poverty alleviation through financial inclusion. The wordles demonstrate the paradigm-shift in this community toward the use of the mobile phone as a financial channel, and a route to financial formalization: that is, toward alleviating poverty by formalizing poor people’s existing informal practices of money transfer, savings and storage.

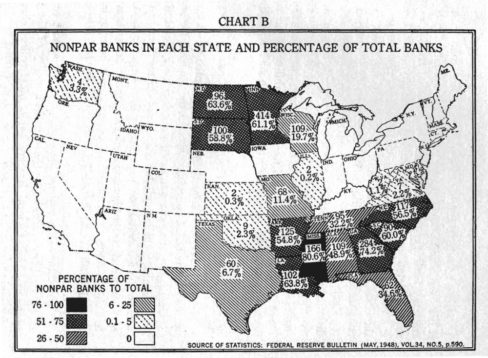

The third image is a map of the distribution of “non-par” banks in the United States, circa 1948. Non-par banks were banks that levied a fee to check a paper check. Rather than settling “at par,” or at face value, the check would clear at a slightly less than par amount. In other words, your check for US$100 might get you only $97 at the bank.

Why juxtapose these images? First, CGAP’s shift in focus represents the insertion of mobile computing into the financial sphere. The mobile’s ubiquity means that more people now have access to mobile phones and signals than they do banks and other formal financial institutions. And unlike banks, mobile phones are also accessible in a second sense: social uses of the phone – phone sharing, SIM-card swapping, airtime topup transfer to another phone – put the device and its capabilities for value transfer within reach of even very poor or isolated people. Married to the dream of formalizing informal financial practices – for safety and security but also for regulation, taxation, monitoring – “mobile money” has been an attractive proposition to development experts and philanthropic agencies. And people already use them for value transfer, sending airtime minutes to one another not just to talk, but as a form of payment or remittance.

So, there is actually promise here. At the same time, the map remind us that the market in payments, in the means of value transfer, has always been a complicated one in which state agencies attempt to create a government-issued means of payment – money – against private interests that would want to own the means of value transfer (see: credit cards!). This is a murky area for much scholarship in the cultural economies of finance only because it has been given so little attention. Our focus on capitalism’s specificities leads us to focus on exchange, and on money as a means of fostering equivalence of exchange. But how the money gets from point A to point B – the infrastructures of payment – have escaped our attention. There is a market in payments, however: the card networks make trillions on small fees levied on transactions (of the same kind that advocates for a Tobin Tax would levy on large-scale financial transactions, but in this case, for the public weal rather than private profit). The US Federal Reserve stamped out the practice of non-par banking in the 20th century, but it was a long, political and technological struggle. And it was immediately rendered moot by the launch of the first private payment system on a card: Diner’s Club. American viewers will also note the legacies of race and class in the US from the map: it was primarily the states of the Confederacy where non-par banking was concentrated.

Finally, we note the juxtaposition of two different visualization technologies themselves. What did this map render visible when it was put forward? What do the wordles render visible? With “hidden fees” in private payment transactions does the politics of visuality still have purchase, or does it limit the critical imagination?